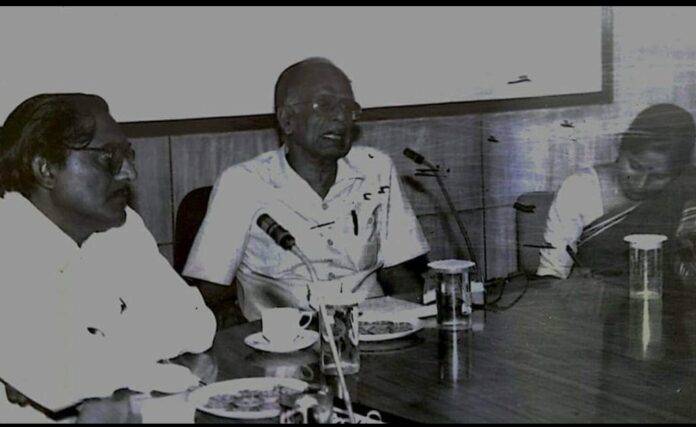

District Collector K.B Bhoge, DGP Shankar Sen and myself, 1999

Around May 1999 I started work in the Chandrapur District Collectorate in a UNICEF supported programme called the Primary Education Enhancement Programme (PEEP) or Amchi Shaka Prakalp in Marathi. At that time there was another programme being implemented called the Swarnajayanti Shahari Vikas Yojana. The District Collector K.B Bhoge combined both the programmes and gave me the job of organising women in Chandrapur city’s slum pockets for educational activities. Sangita Raipure who was tasked with forming self help groups became a good friend and both of us worked well together . I had the full support of my immediate boss, the education officer in charge of the Amchi Shala urban cell Waman Hastak.

Outside Amchi Shala office

Amchi Shala was committed to universal enrollment and offered bridge courses through alternative schools. Through the programme balwadis and informal classes were started in many areas, ration cards distributed in the red light area, alternative schools were started for children of coal miners and a school building was sanctioned in the Nehru Nagar ward.

In between, for some reason which I don’t exactly recall I went to the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) in New Delhi where I met the DGP of NHRC Shankar Sen. We discussed about human trafficking which was a important issue for the NHRC at that time. At the end of the discussion I requested him to come to Chandrapur. A few days later Bhoge Sahab called me to his office and showed me the letter regarding the visit of Shankar Sen to the district. I was given the task of organising a meeting of the DGP with the notables of the city and also a visit to the Balwadi in the red light area.

At that time the Protection of Human Rights Act was six years old but there was little understanding about the legislation and the NHRC was feared as a powerful new regulatory body without a full awareness of its mandate. Therefore we organised a meeting to be addressed by the DGP on the topic of ‘Understanding Human Rights and the Role of the NHRC’. It was a successful programme, held in the district collectorate and well attended by a cross section of society.

A few days after the visit, Bhoge Sahab received another letter from the NHRC. This time he informed me that the NHRC had asked him to appoint me as a district jail visitor to the Chandrapur sub-jail. He issued the required letters and twice a week I started visiting the jail.

The conditions in the jail were pretty bad as one can imagine. I was particularly saddened by the condition of the small children who accompanied their mothers. Three undertrial women, accused of theft, were pregnant. They had already spent four months in the jail and were desperate for release. Every time I went, they beseeched me for help. I spoke to their lawyer who said that their bail application had been rejected. On one of the dates when they were presented before the judicial magistrate I went along and handed the magistrate a letter with my observations. Since I was not a lawyer he was reluctant to accept the letter, but maybe it weighed on his mind as the women were granted bail the next month. There were several other cases where I could not help the undertrials, all of them from miserably poor and marginalised backgrounds, in spite of my best efforts. Whether successful or not I regularly submitted reports to the NHRC with copies to the district collector and superintendent of police Dr. Bhushan Kumar Upadhyay.

The Chandrapur sub-jail used to hold undertrial prisoners several times its capacity. The blackboard at the entrance would have the number of prisoners written for the day. I started noting down the numbers in my diary and thus built a record over several weeks. There was a constable Balu Nimgade who was my teacher about the nitty-gritties of the prison system.

“Why are there so many prisoners from Gadchiroli?” I asked him one day.

“Madam, Gadchiroli district doesn’t have a jail so they use Chandrapur jail,” he explained.

Gadchiroli district had been carved out of Chandrapur in 1982 and yet, I learned, it did not have an independent justice system. I travelled to Gadchiroli and found that there was no district courthouse, there was only one overburdened additional sessions judges and everything operated under the directions of the Chandrapur district court. The irony of the matter was that because of high Naxalite activities, the district had a massive number of criminal cases – far more than Chandrapur. I met the sole judicial magistrate in Gadchiroli and also the Superintendent of Police who shared the problems of coordinating with Chandrapur on all criminal matters. I submitted a detailed report on the grave situation of Gadchiroli’s criminal justice system based on which the Commission issued notice to the State of Maharashtra regarding strengthening of the judiciary in Gadchiroli and budget allocations for courthouse and district prison.

Things were moving along when one day in late August, Vijay Sidhawar who was a reporter with Loksatta in Mul came to my office with some other people from a village called Chitki. They narrated the story of an Adivasi called Gopala Gawde who had had an altercation with his brother over the boundary of their paddy fields. The brother complained to the police who picked up Gopala. They asked him for Rs.5000 and threatened to lock him up if he didn’t pay up. Gopala could not pay the bribe and ended up in jail.

A recent photo with Gopala Gawde, 2018

The next day I took out Gopala’s papers in the jail and learned that he was in jail under preventive sections – Section 107 CrPC. The executive magistrate had noted in his order that the ‘election code of conduct was imposed and the accused should be in custody to prevent law and order problem’. I brought the case to the notice of the District Collector, Bhoge Sahab and requested him for help. On the third day Gopala Gawde was released from prison. The villagers who had come to my office invited me to Chitki.

Those days my father was visiting from Kolkata, so Baba came along to Chitki where the entire village sat on the verandah of Vijay’s friend Ashok Yerme’s house. The programme went on till late at night. Women told us how this was not the first time that the police had asked for money. Then they repeated the familiar story – the patwari asked for money to make mutation entries, there was no work for several months in the year and feeding the children was difficult, the forestwalas chased them when they went to gather fuelwood, there was no road to the village…

“This time I was in the right place in the right time and so I could help Gopala,” I said, ‘but I am not going to be an NHRC jail visitor all my life. Only if we all come together, can we make things better.” In spite of my broken Marathi the message was somewhat understood and the rest was explained by Ashok and Vijay.

Founder members of Shramik Elgar, 2000

Over the next few weeks, the villagers of Chitki village organised and also roped in their friends from the neighbouring village called Ghot. The men and women of these two villages – Chitki and Ghot – with their hard work formed Shramik Elgar, a Sangathan that over the years spread across many villages of Chandrapur and Gadchiroli districts.

Vijay addresses First General Body meeting of Shramik Elgar, 2001

And so it happened that albeit unwittingly, yet in a very real manner, the NHRC contributed to the formation of an organisation that till date remains committed to defending the constitutional and legal rights of the ordinary rural people in these far-flung districts of Maharashtra.

– Paromita Goswami