The Quest for Virakti and Bhagwan

Feature in the magazine ‘Sannyas’ (Nov-Dec.1973)

In today’s world with its constant focus on modernity and scientism, it is difficult to understand the depth of Masa’ab’s constant engagement with religion and spirituality – the manner in which these permeated her private and public lives. The most intense spiritual period of her life was intertwined with an equally intense desire for a son. Pages of her diary are filled with a desire for virakti which appears simultaneously with her ‘search’ for a son. The pursuit of virakti and Vairagya are foundational to both Hinduism and Jainism and are considered stepping stones towards Moksha. Masa’ab sought virakti with an indescribable passion which eventually led to her meeting with Acharya Rajneesh.

Virakti, for Masa’ab comprised of three aspects – Firstly, detachment from luxury. She loved rich clothes, good food, music, dance, poetry. She wanted to detachment from these material things, which she thought only fuelled her pride (ahankar). Secondly, she wanted to reach a stage where her mind would be under her control, where she would not react with anger, hatred and would remain unmoved by respect or disrepect. She wanted to reach samabhaav. And thirdly, she wanted to reach a feeling of all-encompassing love towards all living creatures. (prembhaav).

Masa’ab was equally clear that what she sought would not be bestowed upon her from above and conventional religion did not interest her. She was convinced that virakti would come from self-discipline – anushasan would lead her to virakti. But what was the right method of self-discipline? – she was unsure of that. She realized that social work could not provide the answer – she did it as her duty and also as an experiment (prayog). In fact, she was irritated by people who praised her or put her on a pedestal. She lost interested in travelling and avoided attending public functions. She was consumed with the question of how to reach virakti. She sought answers from many great thinkers and saints of the day. She met Rashtrasant Tukdoji Maharaj and Vairagyamurti Sant Gadgebaba. She often discussed with the Sarvodayi stalwart Shyamsundarji Shukla. She sought out many Jain Rishis and Munis but nobody could satisfy her.

Signals of Things to Come

She remembered a dream she had had at the age of twenty wherein a saffron-clad monk had appeared and said that her son would be a ‘bhagwan’. Now at an age nearing forty, she felt that only her ‘son’ could answer her questions – and she started to ‘search’ for that spiritual son. Throughout her life Masa’ab had many dreams and many unusual experiences that she interpreted as signs of things to come (sanket). Once in a dream she saw a deity who recited a ‘mantra’ and she woke up reciting the last few lines of the same. She travelled to many places – Srinagar, Jaipur, Ludhiana – in search of that mantra meeting many sadhvis and rishis. In Jaipur a mendicant approached her on a road and told her that her search would be over – she would meet the person she was looking for within three months. Masa’ab did not believe the mendicant and spoke rather brusquely with him.

Meeting Acharya Rajneesh

In 1960 she was invited to the sixty-fifth birth anniversary celebrations of a prominent Jain personality Chiranjilalji Badjate which was organized at Bajajwadi in Wardha district by the Bharat Jain Mahamandal. She was depressed and not in a mood to go inspite of Rekhchandji’s coaxing her. It was their family friend Bhikamchandji Deshlahara who finally convinced her to come. Bhikamchandji argued that unless she travelled her twin quests would never be answered. She relented and on 11.9.1960 reached Bajajwadi in Wardha.

It was the second day of the three-day celebration attended by Jain families from many different parts of the country. It was quite early in the morning when they reached and as soon as Masa’ab crossed the verandah of one of the many rooms, her eyes met with those of a young bearded man whose eyes shone brightly. In that electrifying instant, she felt that she had met her son. The man was introduced by Bhikamchandji as Acharya Rajneesh, a professor teaching in Robertson College at Jabalpur.

Masa’ab with Acharya Rajneesh

After lunch she sought him out and found him sitting on the floor of one of the rooms staring into space. She wondered whether he would allow her to enter the room because, in her experience, many sadhaks avoided women as narak ke dwar (doorway to hell). But he not only asked her to sit, they both discussed a few things. She asked why people don’t get what they want, and whether he intended to go to the Himalayas (she preferred teachers who lived amongst ordinary people to those who retreated into the mountains in the most selfish manner). She asked him his age which he refused to answer and finally invited him to Chandrapur. She learnt later that he was twenty-six years old, she was forty.

As part of the birthday celebrations, Rajneesh delivered a sermon which she rather liked. That night a poetry session had been organized. On the insistence of Rajneesh, Masa’ab recited three poems in Hindi which she had earlier read out at a national poetry festival. All three shared the themes of nationalism and communal harmony – azadi mili azad bana, sapno me fir mat kho jana, (we got freedom, we are free, do not fall asleep again) jimmedari desh ki hai, ab to ulajhna chhod de (responsibility of the country is on you, get out of your confusions) and aisa to kabhi hoga hi nahi ke aag se aag bujha lenge (fire shall never put out fire). The poetry session ended at midnight and next morning Rajneesh had left Bajajwadi without meeting Masa’ab. She returned to Chandrapur in a state of confusion.

She narrated the meeting with Rajneesh to her husband and other close family members. She was sure in her heart that he was a son whom she was searching for but she could not be sure. To put her out of misery, Rekhchandji suggested that she should write to him and invite him to Chandrapur. After some hesitation she did write to him but before she could post the letter, she received a letter from Rajneesh’s father. He had written the desire to meet the woman whom Rajneesh had described as his mother from a past life. Masa’ab’s joy knew no bounds. She travelled to Gadarwada and met Acharya Rajneesh’s family.

Understanding Dhyan

Between 1960 and 1964, for as long as Acharya Rajneesh remained in Jabalpur, he became a regular visitor to the home of Masa’ab. He attended the wedding of Sushilakunwar, Masa’ab’s youngest daughter in 1963 and addressed the gathering. It is apparent from Masa’ab’s diary that Rekhchandji Parakh and other family members were impressed by Rajneesh. Rakhchandji would inform interested people in the city and they would all assemble to listen to Rajneesh and also ask him questions. The question-answer sessions used to be quite long. The discussions between Masa’ab and Rajneesh would go on past midnight. Interestingly, Masa’ab does not mention learning anything new from Rajneesh, rather she repeatedly says that he was only saying what she already felt but could not articulate as well as he did.

In this period Masa’ab and Rajneesh exchanged letters regularly which were published as Kranti Beej Seeds of Revolution). The letters in Hindi have descriptions of nature, events, and ruminations on spiritual questions. For instance the following letter was written on the afternoon of 23 August 1961 on a letterhead with ‘Rajneesh’ printed on it and the address 115, Napier Town, Jabalpur (M.P.).

Acharya Rajneesh’s letter to Masa’ab

Ma,

Monsoon flowers are in bloom near the lake under the hills. The lake is filled with lotus leaves and creepers. A couple of empty boats are tied to the lakeside.

The sun is veiled by clouds and we are resting in a mango grove.

How divine is this peace: a bird sings now and then but the peace is not broken by its song rather it only becomes deeper. A silver-haired old man is with me. His entire life was spent without peace (Ashanti). He has everything: nothing is amiss, but all that is meaningless because he has no peace. He has come to ask me how he can find peace. The moment he sat down … even before he sat down, he asked his question.

“The mind is turbulent. I want to make it calm and peaceful. How is it possible?”

I tell him: “The mind and turbulence (ashanti), the mind and unhealthiness (aswasth) – these are not two different things. The mind is turbulent and the mind is unhealthy. As long as it is there, turbulence cannot cease. We have to leave behind the mind; the moment it goes we are healthy…What is the mind? The mind is the process of thinking (vichar prakriya). Thought, thoughts, thoughts – it is the mind that binds one to the other. The mind is not an object, it is a process. There is an empty space in between thoughts – that space contains us. We have to identify that space and stop there. The emptiness is the door which leads to and through which we can reach the ‘I’ (swa). Reaching there we realize there is no mind. Just as the light dispels darkness, the entry into emptiness, in the same way, dispels the mind. The entry into this nullity, this empty space is dhyan (meditation). It is not difficult – it is possible here, this very moment. Be a little aware, and observe not the turbulence (ashanti) but that which is turbulent. As you observe peace rains on the consciousness as rain falls from the clouds. (emphasis in original)

Pranam from Rajneesh

Through years of practice, Masa’ab arrived at her own understanding of dhyan. Dhyan for her was not just something that one did sitting cross-legged on the floor, it was the awareness with which we lived life every moment. She pointed out how in colloquial Hindi the word dhyan was used in an everyday manner. She would point out the importance of dhyan se uthna-baithna, hasna, bolna – doing everyday work with mindfulness.

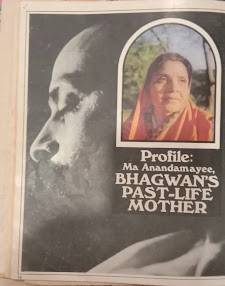

Ma Anandamayee: The Mother of Acharya Rajneesh

In 1973 Masa’ab attended the meditation camp (shivir) organized by Acharya Rajneesh at Mount Abu and here he publicly declared her to be his mother from past life. He touched her feet and gave her the name ‘Ma Anandmayi’. After the camp, she asked Rajneesh what she could do for him and he replied that she could teach his disciples the ‘Indian way of life.’

Kailash Ashram

From Saoli to Usegaon Farm on a Bullock-cart

The Parakh family had 30 acres of land in a village called Usegaon in Saoli block of Chandrapur, next to the banks of the river Wainganga. Rekhchandji and Ma’saab left Chandrapur and started living on the farm. Tarred road stopped at Saoli and they covered the rest of the way on bullock carts. The land had lied fallow for 50 years and with the help of the local villagers it was brought under plough. Between 1973 and 1977 Rajneesh’s disciples came to Usegaon and lived on the farm with Rekhchandji and Masa’ab where they learned cooking, farming and other life skills. Masa’ab notes that many of the disciples who came were from foreign countries and from well-to-do backgrounds, but none of them ever complained of the chores or the hard life on the farm. The Usegaon farm was called as Kailash Ashram those days.

Rekhchandji died in 1980 which was a great blow to Masa’ab. She was in Chandrapur for some work while he breathed his last in Usegaon. Her unhappiness was compounded at the rather disrespectful attitude of her youngest son-in-law. Masa’ab did not return to the farm thereafter. The Kailash Ashram also closed down after Rajneesh set up Ashram in Pune. Masa’ab went to live in Parakh Bhuvan, the old house at Pathanpura, where she stayed the last two decades of her life.

The Last Decades

Till the very end she lived actively, doing every bit of her work herself and then taking care of the cows whose milk she gave to her own family and others. She continued to read and write, filling her diaries and regularly writing letters. She was very fond of her grandson’s wife – her granddaughter-in-law Sonal Parakh whom she called ‘Kunwrani’ and to whom she wrote many letters sharing her thoughts and experiences on many practical aspects of living a good and healthy life. She regularly read the newspaper and diligently marked the portions she thought were important. Her family, extended family and many people in the city sought her counsel on social and spiritual matters. She offered her services to the Jain monks (munis) and nuns (sadhvis) who came to the city.

Author’s Personal Memory of Masa’ab

My own memories of her are limited to a single meeting which took place around seven or eight years ago. The tribal village of Rantalodhi had burnt down completely. This village was earmarked for relocation from inside the core zone of the Tadoba Andhari Tiger Reserve and therefore the government was unwilling to provide any relief to the villagers. I contacted Pankaj Sharma, the Chandrapur district bureau chief of Dainik Bhaskar and explained the situation to him. Through him the matter reached MAsa’ab’s son Deepak Parakh who was an office-bearer of the Jain Samaj committee. On the very same day, Deepakji loaded relief materials in a truck for Rantalodhi. Before leaving Chandrapur city we met Masa’ab. I narrated the horrific situation of the tiny tribal village located in the heart of the thick forest area. She listened quietly and asked me if anyone had died.

“No,” I replied, “thankfully, there are no casualties.”

“Then do your best to help them, but be calm. Remember that if people are alive then all is well. People will always find a way to rebuild their lives.”

Recently, a portion of the Parakh Niwas which had seen many historic meetings including those with Acharya Rajneesh was pulled down and the media reported it with a deep sense of loss. Perhaps if Masa’ab would have been around she would have said that nothing is more permanent than the indomitable human spirit.

Masa’ab left this world at 99 years in March, 2018.

With Masa’ab’s eldest daughter, Shardatai Jain.

– Paromita Goswami

Pranav Jain interviewed his great-grandmother in this video: https://youtu.be/s7eawSrr9KU